Lower Price Hill and Queensgate: The Power of Transformation

- Anthony Gustely

- Nov 15, 2020

- 6 min read

It's week 9 of 52 First Impressions and I'm 18 neighborhoods deep. I'm nearly done with my visits to the West Side, with just Camp Washington left to visit in the area west of I-75 and south of I-74. This week, my good friend Nicole tagged back along to visit the iconic Cincinnati Museum and a couple other landmarks. Queensgate and Lower Price Hill are interesting neighborhoods because they've both undergone dramatic shifts over their histories. Let's get into it:

Lower Price Hill

Although tied to Price Hill through the name, Lower Price Hill wasn't actually thought of as being apart of the Price Hill history until the turn of the 19th century. Before this time, its proximity to the Mill Creek defined it as a residential community for those who worked in the transportation and industrial sectors.

Geographically, Lower Price Hill is the one Price Hill neighborhood that lies at the foot of the hill. Situated between the Mill Creek and the other Price Hill's, Lower Price Hill is one of the smallest neighborhoods in Cincinnati with 1,075 residents. Its business district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places with 196 historic buildings.

Of its 291 households, 1/3 make less than $10,000 per year, while 2/3 make less than $20,000 a year. Per the 2010 Census, the median household income of Lower Price Hill was $15,257. It's a stark contrast with its uphill neighbor, East Price Hill, whose median household income for the same year was $28,425.

Although it's known somewhat of a gateway to the West Side, Lower Price Hill is significantly cut off from every single surrounding community. To the east, Gest Street and 8th Street run over the top of the Mill Creek and Queensgate's many freight lines. To the west, the Hill is both a visual and elevational barrier, making it difficult to connect East and Lower Price Hill. To the north, the neighborhood tapers off: industrial use caps the neighborhood and roads circle back (only State Road runs out of Lower Price Hill to the north). The busy U.S. Route 50 caps the southern boundary of the neighborhood. 3 residential streets actually still abut U.S. 50, a couple metal stakes creating a close and sheer barrier between the two.

Driving around Lower Price Hill, Nicole and I realized how dense the building footprint of the neighborhood was. Despite being cut off from other communities, the bones of Lower Price Hill's urban fabric has been well preserved. Although many storefronts in their commercial district sit vacant, we saw a few businesses getting ready to open (a great sign!). Additionally, the Oyler Elementary School (CPS) is a Community Learning Center, serving as an anchor institution for the neighborhood. Adelyn Hall, the Director of Housing and Neighborhood Development for the Community Learning Center Institute, a community learning center is a conglomerate of co-located public/private partnerships responsive to the vision and needs of a CPS school and its neighborhood.

I invite you to check out the Lower Price Hill Resurgency Plan. With over $100 million in community improvements since the 2015 plan, $20 million has come directly from the plan, including a million dollar bike trail that will eventually connect to downtown, a fresh grocery project, new housing in partnership with Habitat for Humanity, and environmentally safe jobs.

Queensgate

Of all neighborhoods in Cincinnati, Queensgate has probably undergone the most dramatic of transformations in under 75 years. Once a bustling neighborhood, Queensgate is now the smallest neighborhood in population, with just 142 residents.

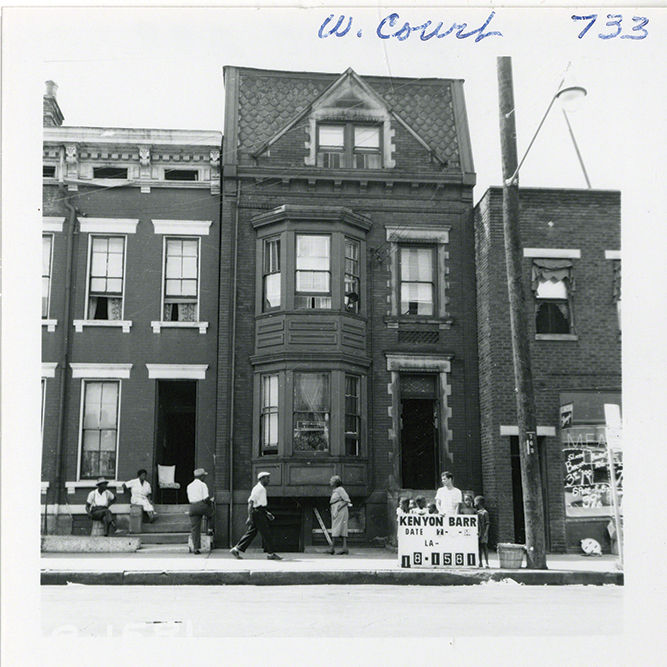

Present-day Queensgate was formerly known as the dense Kenyon-Barr neighborhood in Cincinnati. As a part of the West End, Kenyon-Barr was the heart of the black community inI the Queen City. In 1958, 25,737 people lived in Kenyon Barr: 5 percent of the city's population at the time. A large urban renewal and slum clearance project, Queensgate I, displaced all 25,000+ residents in Kenyon Barr as a result of the City's 1948 Master Plan. 97.7% of residents were black.

As far as how the residents of Kenyon-Barr were informed, the notice came in the mail on city letterhead: “The building which you occupy has been purchased by the City of Cincinnati. […] Now that you have received this letter you should start looking for another place to move immediately. […] ALL OCCUPANTS OF THIS PROPERTY MUST MOVE.” The message put any hope of a reversal of fortune on ice. It was signed, “Very Sincerely Yours, Wanda W. Dunteman, Supervisor of Relocation and Property Management.” - "25,737 People Lived in Kenyon-Barr When the City Razed it to the Ground", Cincinnati Magazine

I highly encourage you to check out the article about the Kenyon Barr neighborhood here. It details the specifics of a neighborhood in its prime before the City demolished it and razed an entire community.

Although dominated by industrial use today, including a slew of freight lines, rail yards, factories, and storage facilities, the Cincinnati Museum Center is the crowned jewel of the neighborhood. The magnanimous Art Deco building was originally called Union Terminal, and first opened on March 31st, 1933 to serve as a central train station for Cincinnati residents. Constructed during the decline of train travel, the costs of the building almost immediately outnumbered its benefits for the City. As train travel continued to decline in the 50s and 60s, the construction of Interstate-75 cut Union Terminal off from the rest of downtown Cincinnati. Fun fact: in the 1970s, University of Cincinnati graduate students were actually credited with saving the terminal from demolition! Today, Union Terminal now serves as the location for the Cincinnati Museum Center and the Amtrak passenger train service.

Growing up in Cincinnati, Nicole and I LOVE the Museum Center. Separated into two different sides, the Cincinnati History Museum and the Museum of Natural History & Science, we had such a great time re-exploring our childhoods and finding our inner kid again. Starting with the Cincinnati History side, we began with the scaled model of Cincinnati from the 1940s (Nicole and I both agree this is our favorite part of the entire museum). The intricately detailed model includes downtown Cincinnati, OTR, and glimpses of Price Hill and Mount Auburn as well. It truly is an amazing site: I'd argue that no picture truly does the massive model justice. Every time I look at it in person, I find something new.

Since I had last been to the Museum Center, they had remodeled the Cincinnati History exhibit to frame a timeline of the City's history within the context of transit development (very clever!). The exhibit walks you through indigenous transportation, the invention of the steamboat, steam engine, passenger train, streetcar, and automobile. If you've been following along for a while on this blog then you know that the establishing specific transit networks in American Cities (*cough* The Interstate Highway System *cough*) displaced thousands and thousands of low income and minority residents in the process and wrecked any chances of building generational wealth through home ownership, so I was disappointed when there was only a tiny blurb about it in the exhibit.

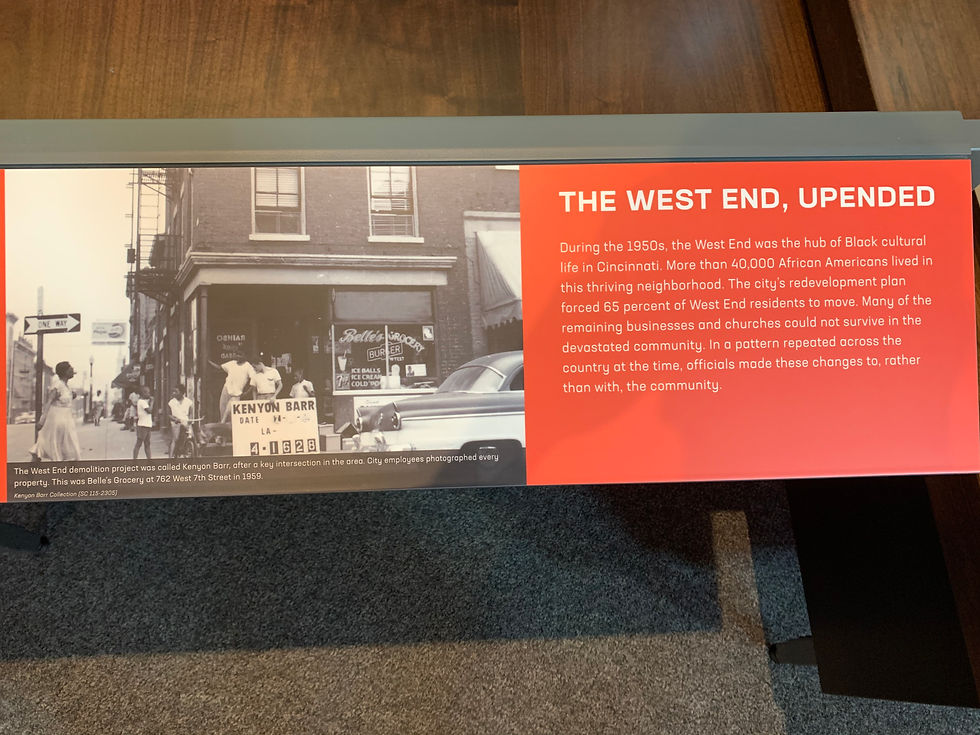

I understand that there's maybe a sense of needing to glamorize and hype up Cincinnati's history to showcase the good, but it does a great disservice not to point out mistakes in the process of city-building and educate the public. The blurb pictures below says this:

During the 1950s, the West end was the hub of Black cultural life in Cincinnati. More than 40,000 African Americans lived in this thriving neighborhood. The city's redevelopment plan forced 65 percent of West End residents to move. Many of the remaining businesses and churches could not survive in the devastated community. In a pattern repeated across the country at the time, officials made these changes to, rather than with, the community.

Maybe it's just ironic to me that the Museum Center sits in the vicinity of a once-thriving Black neighborhood and the least the Museum Center could've done is given more than a paragraph about what's happened historically with the destruction of a vibrant community (and what may happen again with the FC Cincinnati Stadium in the West End, ope).

Nicole and I also enjoyed the Natural History & Science side of the museum. One of my personal favorites of the museum, the Bat Cave (which mimics an underground bat habitat/cavern situation), was closed due to COVID-19. I'm looking forward to coming back once the pandemic is over to fully appreciate all of the recent renovations made over the past couple years!

These past couples weeks I have been extremely busy finishing school projects and balancing extracurriculars in the process. Unfortunately, I tested positive for COVID-19 this past week, so it's going to be a couple weeks until my next blog post. I'll be visiting Camp Washington, Winton Place, and Winton Hills, and will most likely be eating some chili and discussing environmental justice in the process. Hang tight and I'll talk to you soon :)

Comments